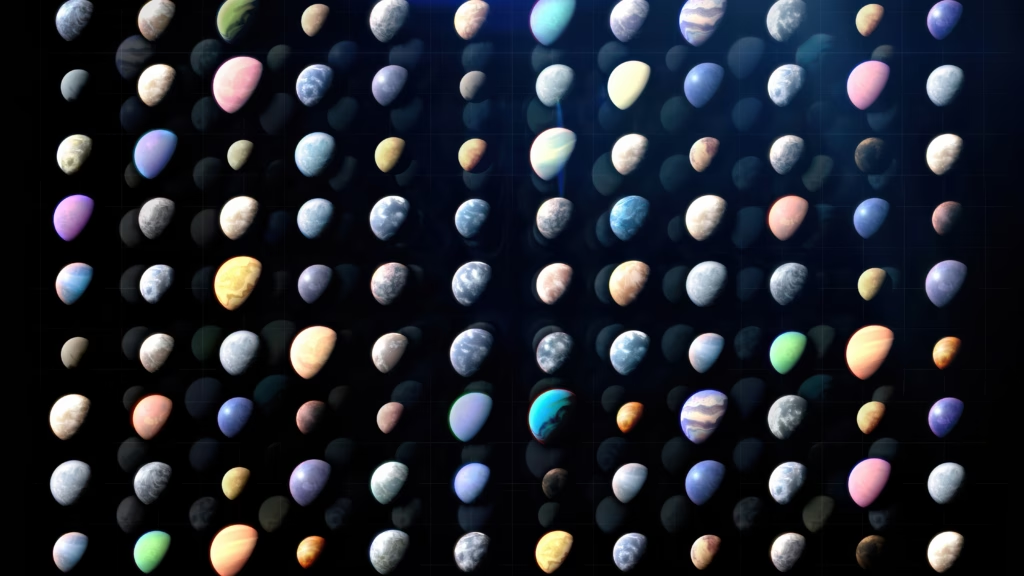

Imagine looking up at the night sky and realizing that almost every twinkling star you see could have its own planets orbiting around it. For decades, this was mostly the stuff of science fiction, but today it’s a reality we’re watching unfold before our eyes. NASA has just confirmed that the official number of known exoplanets—planets beyond our solar system—has reached 6,000. That’s six thousand worlds, each with its own unique story, spinning silently out there in the galaxy.

What makes this moment so exciting is not just the sheer number, but also the journey it represents. Thirty years ago, in 1995, scientists confirmed the very first planet orbiting a star like our Sun. That discovery opened the floodgates, and now, just three decades later, we’ve built a catalog that’s rewriting everything we thought we knew about the universe.

And here’s the fun part: the number isn’t slowing down. More than 8,000 candidate planets are still waiting for confirmation. Think of it like a giant “pending” list of possibilities. Every new telescope, every fresh mission, brings us closer to uncovering entire solar systems we’ve never imagined.

The Significance of the 6,000 Milestone

When NASA’s Shawn Domagal-Goldman announced the achievement, he described it as the result of “decades of cosmic exploration driven by NASA space telescopes.” That phrase captures the heart of this milestone. It’s not just about logging numbers; it’s about transforming how we see the cosmos.

Before these discoveries, our picture of the night sky was simple. We knew planets orbited our Sun, and we had learned a lot about them—some rocky, some gaseous, some friendly to life, others hostile and barren. But beyond that, everything was speculation. Were we rare? Was Earth a cosmic fluke? Or were there countless other worlds out there, waiting to be found?

Thanks to missions like Kepler, TESS, and the James Webb Space Telescope, we now know the answer: planets are everywhere. Big ones, small ones, strange ones, familiar ones—the universe is teeming with them.

Domagal-Goldman put it beautifully when he said that all of this leads back to one of humanity’s most fundamental questions: Are we alone? With upcoming missions like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the Habitable Worlds Observatory, NASA is preparing to take the next leap—searching not just for planets, but for worlds that might be a lot like our own.

From the First Exoplanet to Thousands More

It’s worth pausing to appreciate how quickly this field has grown. The first confirmed exoplanet orbiting a star like our Sun was spotted in 1995. That was just one planet, a lonely dot in the data.

Now, three decades later, we’ve cataloged 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, with thousands more on the way. That’s an astonishing acceleration of discovery. And each planet isn’t just a number—it’s a world with unique conditions, waiting for us to study and understand.

Some of these planets are rocky, like Earth and Mars. Others are gas giants, more like Jupiter and Saturn. And then there are the weird ones that don’t resemble anything in our solar system: hot Jupiters that orbit so close to their stars they complete an orbit in just days, planets orbiting two stars like something out of Star Wars, and even worlds with clouds made of gemstones or surfaces covered entirely in lava.

Every one of these discoveries adds a brushstroke to the larger cosmic painting, helping us understand not only how planets form, but also how common Earth-like worlds might be.

What We’ve Learned About Planet Populations

So, what have we discovered so far? Our own solar system offers a nice balance: four rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars) and four giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune). But the universe seems to prefer rocky planets.

That’s right—small, rocky worlds like Earth are much more common than we once imagined. This is thrilling, because it means that Earth-like planets may not be rare at all. In fact, they could be sprinkled generously across the galaxy, orbiting stars of all types.

We’ve also found plenty of exotic surprises. Imagine a planet that’s as light as Styrofoam, so fluffy it seems like it shouldn’t exist. Or a massive gas giant orbiting closer to its star than Mercury does to our Sun, roasting in unimaginable heat. We’ve even spotted planets that orbit dead stars, planets with no stars at all, and even systems with double or triple stars. The universe is endlessly inventive.

As Dawn Gelino, head of NASA’s Exoplanet Exploration Program, explains, each new type of planet tells us something important. By studying these worlds, we get a clearer picture of where to look for Earth-like planets—and ultimately, where we might find signs of life.

The Challenge of Discovering Exoplanets

If planets are everywhere, why did it take so long to find them? The answer is simple: they’re hard to see.

Planets don’t shine with their own light; they reflect the faint glow of their stars. And when you’re looking across light-years of space, that glow is incredibly faint. Most planets are drowned out completely by the blinding brightness of the stars they orbit.

That’s why only a small fraction—fewer than 100—have been directly imaged so far. Instead, astronomers rely mostly on indirect methods. One of the most successful is the transit method, where telescopes watch for tiny dips in a star’s brightness when a planet passes in front of it. Another is astrometry, which looks for the subtle “wobble” a planet causes in its star’s position. And then there’s gravitational microlensing, which uses the bending of light caused by gravity to reveal hidden planets.

But spotting a candidate planet isn’t the same as confirming it. To be sure, scientists need follow-up observations, often from multiple telescopes. That’s why NASA’s Exoplanet Archive still has thousands of “candidates” waiting for confirmation.

As Aurora Kesseli from NASA’s Exoplanet Archive explained, this is where collaboration becomes crucial. Scientists across the globe work together, building tools and pooling data to turn candidate planets into confirmed ones. The more eyes on the sky, the faster the discoveries pile up.

A Surge in Discoveries

The pace of discovery has been breathtaking. Just three years ago, the official count hit 5,000. Now we’ve added another thousand, and the curve shows no signs of slowing.

One big reason is the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, which uses astrometry to track stars with astonishing precision. Gaia is expected to deliver thousands of new exoplanet candidates. And then there’s NASA’s Roman Space Telescope, set to launch in the coming years, which will bring even more discoveries using gravitational microlensing.

Every new mission adds a new tool to the toolkit, and with each tool, our vision of the galaxy becomes sharper and more complete.

The Search for Earth Like Worlds

At the heart of all this excitement is one big dream: finding a planet that truly resembles Earth. A rocky world, orbiting in the habitable zone of its star, with conditions that could support life.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has already made huge strides in this direction by analyzing the atmospheres of over 100 exoplanets. That’s important because atmospheres can reveal biosignatures—chemical clues that life may exist or once existed.

But here’s the challenge: studying atmospheres of Earth-sized planets is really, really hard. The glare from their stars is so overwhelming that it drowns out almost all the signals we want to see. To put it in perspective, the Sun is about 10 billion times brighter than Earth. If some distant astronomer were looking our way, Earth’s faint light would be almost impossible to detect against the solar glare.

That’s why NASA is investing in new technology, especially coronagraphs—devices that block out starlight so telescopes can spot faint planets nearby. The Roman Space Telescope will carry a coronagraph demonstration, which could directly image planets the size and temperature of Jupiter. It’s a huge step forward, even if it doesn’t quite get us to Earth-like planets yet.

The next big leap will come from the Habitable Worlds Observatory, a future mission concept designed specifically to hunt down Earth-sized planets and study their atmospheres. With each new advance, the dream of finding another Earth inches closer.

The Promise of Discovery

So, where does this leave us? With 6,000 confirmed exoplanets and thousands more waiting in the wings, we’re at the beginning of a new golden age of discovery. Each planet adds to our cosmic story, showing us that the universe is more diverse, more fascinating, and more alive with possibilities than we ever imagined.

And while the numbers are thrilling, the real magic lies in the questions we’re starting to ask. What makes a planet habitable? How common are Earth-like worlds? Could life exist in forms we’ve never considered? And most importantly, are we truly alone?

NASA’s exoplanet missions—past, present, and future—are working toward answers. The Roman Space Telescope, the Habitable Worlds Observatory, and other groundbreaking projects will continue to push the boundaries of what we can see and know.

One day, we may open the archives and see not just a number like 6,000, but the confirmation of something far greater: the discovery of life beyond Earth. Until then, every new planet is another step on that journey.

Final Thoughts

When you think about it, 6,000 planets isn’t just a statistic—it’s a reminder of how far human curiosity can take us. In just 30 years, we’ve gone from knowing of no planets outside our solar system to building a library of thousands. We’ve discovered worlds stranger than fiction, built telescopes that can peer across unimaginable distances, and developed tools that bring us closer to answering the oldest question in the book.

The night sky has always inspired wonder. But now, thanks to NASA and the global scientific community, it inspires something even greater: the realization that our universe is full of worlds, and perhaps, someday, neighbors.

So, the next time you look up at the stars, remember—there are at least 6,000 planets circling them, and that number is only growing. Somewhere out there may be a planet not so different from ours, waiting to remind us that we’re part of something vast, beautiful, and connected.

Source: NASA

2 comments

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something.

I think that you could do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit, but other

than that, this is great blog. A great read.

I’ll certainly be back.

https://ww1.datakeluaranhk.buzz/

WOW just what I was looking for. Came here by searching for news articles for students

http://w2.masterbbfs.cfd/